The is No Right Answer

In the last few weeks, I have had to revisit two of the most important lessons I learned when I started teaching comparative politics classes exactly fifty ago next month.

Right and Wrong

The first is embedded in this post’s title. From the beginning, I used a line like “there is no right answer” whenever I gave my students a complicated topic to write about. For example, I routinely asked students in an introductory class to assess the differences between a presidential system like our own and the parliamentary ones used by most other democracies.

I had to stress that there were no right answer….

Especially if they had to write about something controversial.

And super especially if they weren’t going to agree with me.

My statement came with some qualifications.

There were wrong answers that included glaring factual errors about, say, the role of party discipline in the British House of Commons.

And some answers were better than others because, for instance, when students included nuances like the difference between three line whips and free votes. In the latter, MPs are literally free to vote their conscience. In the former, if their own beliefs led them to break with their party’s leaders, they jeopardize their entire career.

It Was Not About Me

At the time, I had to learn something else that still have to work at mastering.

Whether as a faculty member or, now, as a political organizer, one of the most important things I learned was the importance of keeping my ego under control

What happened in classroom wasn’t about me.

My job was to help my students grow.

If and when I obsessed about what I was getting out of the experience, it came at their expense. To take the most obvious example, if my main goal was to “profess” and wow them with how much I knew, they didn’t think much. At best, they parroted “my brilliance” back at me and wrote humdrum answers about parliamentary and presidential systems that they did not enjoy writing and I did not enjoy reading.

On the other hand, when I focused on their growth and then could see the tangible impact that I was having on them, I got all the feel-good moments I could have ever asked for.

The same thing has held in my political work. Rarely have I gotten very far by trotting out everything I know about peacebuilding when dealing with a skeptic. But if I engage in a dialogue, make it clear that there are no totally correct answers, and ask them to tell me more about why they think the way they do, I can get somewhere.

There Are No Right Answers For My Job Today

In the last few weeks, I’ve realized that the time has come for me (re)learn those lessons as my own career takes off in a new direction.

This time, it’s not about the ways twenty year olds make sense of different kinds of political systems but about how I go about changing our own.

Now that I have finished writing Peacebuilding Starts at Home and turn my attention to building the movement of the same name, my political role will change.

The book lays out what I think is the best strategy for building peace here at home given the circumstances we find ourselves in as the first quarter of the twenty-first century draws to a close.

There’s no need for me to into it in more detail here, since I’ve written about it a lot over the last few weeks and will do so even more as the publication date for Peacebuilding Starts at Home nears.

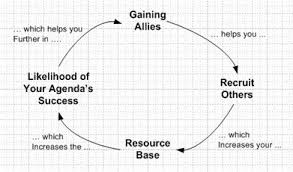

It’s the movement building part of my job that I have pay more attention to now. In order to do so, I need limit the impact of my political ego which is another way of saying that I have to pay a lot more attention to the ideas my colleagues put forward that are not exactly the same as mine but which we will need to create the support the paradigm shift I have been working for since I started working for Beyond War forty years ago—if not before.

As I reminded my therapist a few weeks again there never was a single new left movement in the 1960s. Rather, there was a lot of smaller movements . Their leaders disagreed on goals and strategies but came together from time to time for massive mobilizations against the war in Vietnam and the like. Most of the time, they did their own thing.

At the same time, we all felt as if we were part of “the movement” even if no such thing actually exited.

In the end, we will have to create something like that 2020s style in which veteran activists like me who also can “see” across ideological, issue-based, and demographic divisions help create something even bigger and more coherent than anything we dreamed of sixty years ago.

So, I will have to spend the next chunk of my professional life navigating between supporting a point of view that I have spent a lifetime developing and the need to build a coalition that includes people who don’t share everything I believe in but that we will need if we want to pull off my beloved paradigm shift.

And if that is the political challenge I now have to take on, there definitely are no right answers, and definitely have to embrace views that are not the same as mine.

Thanks to Ola Mohajer, Vinay Orekondy, Joan Blades, and My Blended Family

Over the last few days, I’ve come to realize that I actually have a pretty good idea about how I could pull that off precisely because I’ve been doing something like it for my whole adult life.

I only saw that because I had a pair of conversations with people I’ve just met along with another pair with people I’ve known for decades.

I met Ola Mohajer at three events on consecutive days in late June. All dealt with entrepreneurial approaches to peacebuilding. At the time, Ola was in the process of resigning from the United States Institute of Peace so that she could focus on Transcend, a startup she created to use AI to help peacebuilders design their projects and otherwise enhance their work.

I had long been interested in AI but had had my doubts until I sarated playing with Notebook LM and Perplexity. Still, I didn’t imagine that I would end up pursuing it in my own work. When I saw her pitch deck, I finally saw how AI could help peacebuilding. I then spent some time seeing how Transcend’s tools work. Within six weeks, Gretchen and I had decided to become angel investors in her firm because I had come to realize that we couldn’t build the kind of movement I envision without AI.

So, I began seeing how my role could easily expand.

It was only three weeks ago that I met Vinay Orekondy at the International Listening Association conference. I sat in on his presentation the first day when he talked about the civic hubs that his team at Better Together America were creating. I knew immediately that his work was important because I assumed that AfP’s Peacebuilding Starts at Home team would have to create something like them. Now, I found that Vinay’s and tea team were already creating them.

The challenge was that they were doing it in part through the so-called bridging community whose general strategy has always struck me as too timid because its members focused (too much) on getting people who disagreed to talk with each other. Yet, here Vinay was building precisely the kinds of coalitions we needed to make. And, he was speaking my language about how social and political change occurs.

So, I saw, again, how my role could expand—in this case, because I wouldn’t have to do everything because other people did a lot of things far better than I ever could.

I’ve also found myself talking a lot these days with Joan Blades, co-founder of Living Room Conversations and a stalwart of the Bridging community. Joan and I have known each other for years, and our connections go beyond politics because she plays in a weekly intergenerational soccer game with one of my college roommates.

As much as I like Joan and respect her political history that includes co-founding Move On and Mom’s Rising, I had a tendency to think of her just as a a bridging person—albeit an amazingly thoughtful, soccer playing one.

But as we have talked after she read my book in draft form, I’ve realized that we have similar interests in entrepreneurship and the role that technology can play in our work. Even more importantly, given her history both in politics and business, we share many of the same interests in large scale social change that dwarf my qualms about parts of the bridging so community.

And I learned once again how my role needs to expand by rethinking my relationship with the people I work with.

The last set of conversations all took place at our blended family’s weekly cookout. Ever since the pandemic began, Gretchen’s first husband, Ed, has been grilling for us all in their daughter’s (my step-daughter’s) backyard whenever the weather and our schedule permits.

As is often the case, this Sunday’s discussion included social and political issues and the challenges the country and the world faces under the second Trump administration. Oddly, I find myself the most conservative person around the grill. Ed has participated in a number of No Kings and anti-Musk rallies. Then, this weekend, he, my step-daughter, and her husband all said that they didn’t see much hope and that it would be up to my grandkids’ generation to get things right.

I protested. I don’t think that it is morally acceptable to abdicate on our responsibilities.

At the same time, I also had to admit that the kids of strategies that we are developing with Peacebuilding Starts at Home are likely to appeal to them.

So, if I want to put my clichéd money where my clichéd mouth is, I have to provide them with on-ramps into active engagement even if they were things I wasn’t like to be do myself.

In short, once again, I learned that I have a lot to learn.

A line I used to use all the time when I gave a test or assigned a paper topic.

Next Steps

Then, yesterday, I attended a discussion of the future of publishing led by one of my favorite authors, Steven Johnson, whose Where Good Ideas Come From had a huge impact on my thinking when I first read it a decade or more ago. In it, Johnson talked about an idea of the adjacent possible that was first developed by the evolutionary biologist Stuart Kauffman.

Essentially, species evolve not by taking radical leaps into the unknown. Rather, they make small changes—the adjacent possible—that can, in turn, lead to even bigger changes down the line.

In my case, that means building partnerships with the likes of Ola, Vinay, Joan, and my family members in which we find common cause by working together and exploring our differences as well as our similarities. And keep expanding the adjacent possibles until we build a coalition that includes more and more of those Americans who come to understand that we need my beloved paradigm shift.

But I’ve run out of room here. So, you’ll have to wait until next week to see why that’s the case and how we need to learn that lesson that extends far beyond any classroom I ever taught in.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Alliance for Peacebuilding or its members.

There is no?